How We Made Playable Quotes for the Game Boy

Imagine there’s a specific moment in a Game Boy game that you want to share with a friend. You could share a screenshot or a video, but that’s not the same as letting your friend grab the controls and try it for themselves. Many Game Boy emulators have a notion of a save state file, but in order for your friend to use one of these, they need to have access to the original game. It would be overkill (and likely illegal) to post the entire original game just so that your friend can play for a few seconds. What if you could share a playable quote from the game in the way that you can share readable quotes by just copy-pasting the specific text you want?

With Playable Quotes for Game Boy, you can create and share tiny interactive slices of existing games. Simply load your game into the Playable Quotes emulator, play towards the part of the game you want to demonstrate, click the “Record New Quote” button, continue playing, then eventually click the “Stop recording” button to complete the demo. Once that is done, you’d get a file that contains just enough of the game to recreate all the moments in the game between when you clicked the “Record demo” button and the moment when you hit the “Stop recording” button. Others can now watch your quote as if it were a video, or decide to grab the controls at any moment and explore the impact of their own choices.

In this post, we (Joël Franusic and Adam Smith) will go into detail about how we created Playable Quotes.

This is a long post, so we’ll start with an overview of what we’ll be covering:

- What is a Playable Quote?

- What can you do with a Playable Quote?

- How We Made Playable Quotes

- Suggestions for Future Work

- Advice

- Thanks

What is a Playable Quote?

In its most basic form, a Playable Quote is two things:

- An emulator save state

- A sliced game ROM that contains only the data needed for the quote

The save state contains the entire state of the emulator from the moment that the “Record New Quote” button was clicked: CPU register values, the stack pointer, the program counter, timers, the real time clock, all of various RAM elements, etc.. You can think of the save state like a bookmark in the space of play for that game. If someone else has the book/game, the bookmark will get them to the passage you want to quote.

The sliced game ROM is similar to the original game ROM, except that every part of the ROM that was not accessed during the recording of the Playable Quote is set to zero. You can think of the sliced ROM like a book with most of the pages curiously blank except for those needed to read your quote. If you start reading at the bookmarked location, you’ll immediately get the desired content. You won’t notice that the rest of the book was blank until you start reading outside of the bounds of the quote.

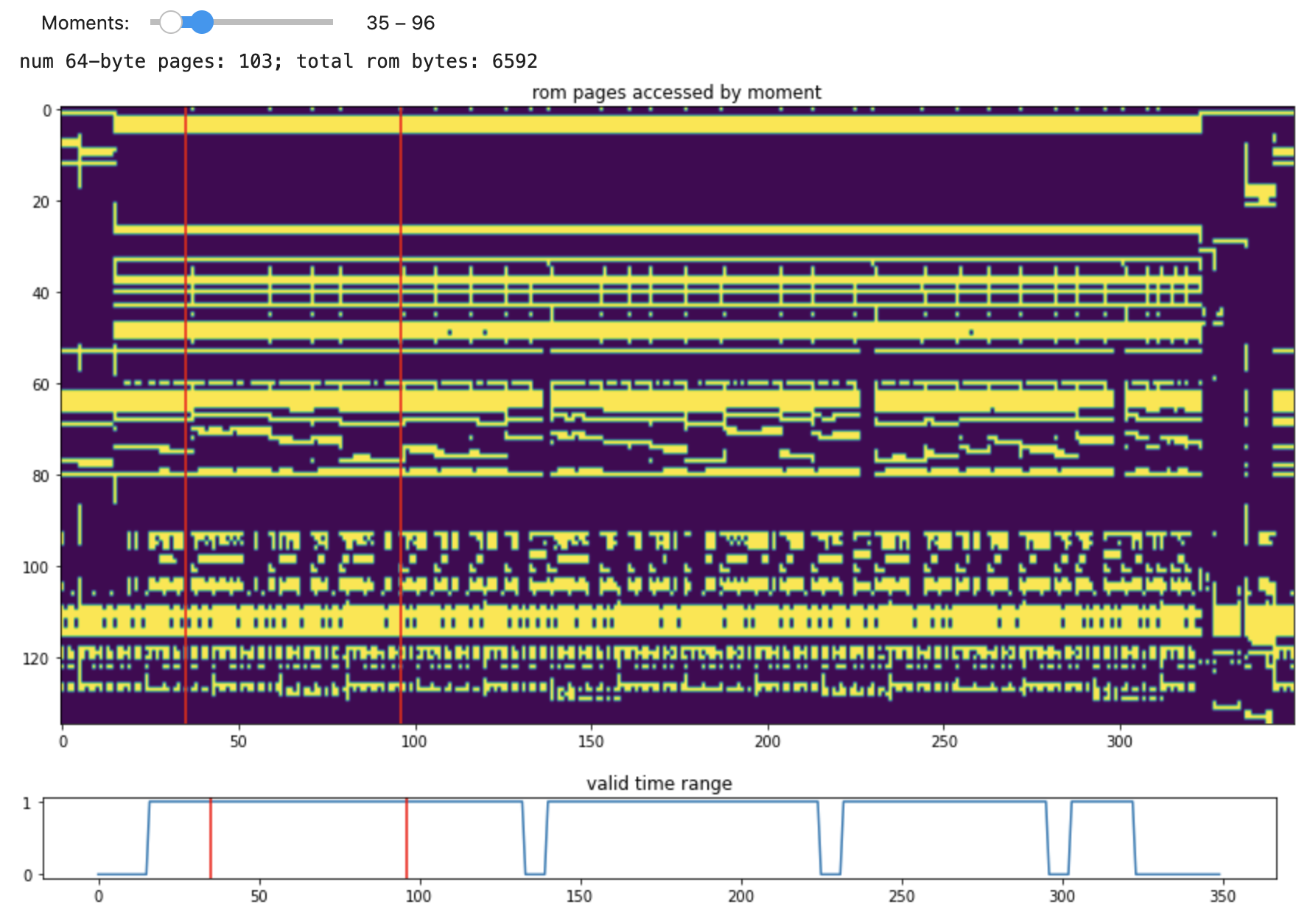

To illustrate this, look at the two images below. The first image, on the left, is a visualization of the game ROM for Tetris. The second image, on the right, is of the sliced game ROM:

Each pixel in the images above represents one byte. Bytes representing zero (0x00) are colored black and every other byte is colored according to the “jet” colormap. As you can see, the sliced game ROM on the right is mostly zeros. While the original ROM on the left has hardly any black at all. (We store a byte-validity mask separate from the ROM so that we can distinguish valid zeros from the zeros we use to blank out irrelevant ROM segments.)

Beyond the save state and the sliced ROM, we store a few additional pieces of data inside of our Playable Quote files. We’ll cover these below. All of the components of a Playable Quote are assembled into a ZIP file. We then steganographically encode into an intuitively sharable PNG file.

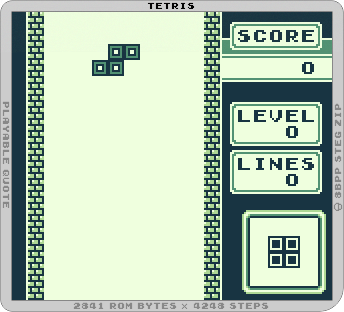

Here is a quote for the game Tetris (you can clear a few lines at a time, but you can’t leave the main game mode or clear four lines at a time):

What can you do with Playable Quotes?

Using the tools we have made so far, you can use Playable Quotes to create, play, and share moments from almost any Game Boy game (not every game is fully supported by the emulator we decided to build on). We hope that people will make use of these tools to do things like:

- Reference specific moments of games in academic and professional settings.

- Create focused demos that entice players to engage with the full games.

- Add Playable Quotes to videogame walkthroughs, reviews, or game wikis.

- Create speedruns that focus on the percentage of the ROM touched.

- Create related tools to reduce the size of existing software.

- Conduct research towards playable quotes for mobile apps (e.g. Android/iOS).

- Create tools to help developers better understand existing code.

- Create tighter feedback loops in software testing.

For the moment, we’re only demonstrating Playable Quotes of Game Boy games. However, the concept generalizes to many other systems (so long as there is an existing notion of a save state and bulk memory/storage to be sliced). In the future, we’d like to see the idea extended to a long tail of game platforms like the SNES, Z-machine, SCUMM VM, MAME, Apple ][, Docker, X86 emulators (QEMU, Bochs, DOSBox, etc). We’d also like to see the idea scaled up to full desktop platforms capable of quoting from current and future software for 64-bit operating systems.

Do you have ideas for improving the interaction experience of creating and using a playable quote or know how to demonstrate the technical ideas on top of other platforms? We’d like to get others working on this idea with us. (That’s a big reason for writing this article!)

What follows is a detailed story of how we built Playable Quotes, from conception to the website that you see today at https://tenmile.quote.games

How Playable Quotes were made

The concept behind playable quotes could have been realized decades ago, but ideas like this rarely spring into existence in an organized manner. If you’ll allow some simplifications, the story of how we made Playable Quotes divides organizes into four coherent chapters:

- Conception

- PyBoy Hacks

- Tenmile Vision and Prototype

- Production Mode

Conception

The concept for Playable Quotes came from Adam Smith. It extends research being done in Adam’s Design Reasoning Lab on making search engines that understand that games and other interactive media contain a vast space of possible moments (like the collection of paragraphs in a book). It also connects to his desire to be able to share moments in games with the students in his various game design classes and for the younger students to be able to share back relevant moments from their own generation of videogames.

Joël was drawn to the idea because of his interest in making “all software, from all time, instantly available for use by any programmer” and also because he wants to learn more about the Game Boy architecture (he has a hypothesis that it should be possible to make Game Boy hardware with one-hundred hours of battery life).

We had spent many months casually kicking the idea around, but due to various reasons we weren’t able to actually work on the project until earlier this summer, in part because Joël was on a sabbatical from his job at Okta and Adam was on a summer break from teaching at UC Santa Cruz.

On June 30th, about a month after the start of Joël’s sabbatical, Adam set up a meeting for us to get started. In the meeting, we slapped a Google Doc together with all of our inspirations, known prior art, motivations, and (most importantly) a plan for how to get started.

Our inspirations included the snippets that Google includes in search results; the court ruling that made it clear that Google’s use of book snippets constituted fair use; the in-depth disassembly and commentary of the Game Boy ROMs for Pokémon Red and Blue and Super Metroid; the “virtual game museums” for lockpicking mechanics, digital water, three-dimensional video game level maps, and two-dimensional video game level maps.

Looking at how people share specific interactions of larger software, we spotted Apple’s “App Clips”, Google’s “Google Play Instant”, and WeChat’s “App Mini’s” which we found interesting and inspiring, if only distantly related to what we had in mind. These are closer to the traditional method of asking developers to create a special demo version of their software and quite far from the experience of quoting a book.

According to our initial plan, we should find and modify a Game Boy or SNES emulator to print out a CSV file of every memory transaction and every button press. The range of unique addresses seen in this transaction log would allow us to estimate how small a quote might be relative to the size of the original game. We picked the Game Boy and SNES as target platforms for their relative simplicity compared to modern hardware, but also because of the strong nostalgic motivation that those platforms have for each of us. This nostalgia isn’t relevant for Adam’s students, but it might help communicate the idea to peers in our generation.

Now that we had identified a concrete first technical step, it was time to get started.

PyBoy Hacks

We both started work the next day. Adam had found PyBoy, a Game Boy emulator written in Python and made some promising early progress in his experimentations. Also a big fan of Python, Joël decided to try it out too.

After wading through the codebase for a while, we found the CPU core and the lines where memory addresses were being formed before being sent out on the memory bus. We made fast progress and with a modification to PyBoy, we had a CSV file of all memory accesses from a short period of gameplay. Compared to the size of a typical Game Boy game (a few hundred kilobytes) the transaction log file for a minute or so of play was huge (227MB)!

We took different approaches to analyzing the data: Joël wrote small Python scripts to perform analyses and Adam took the more elegant approach of using a Jupyter notebook and rendering colorful charts.

One of our first sanity tests on the data yielded unexpected results. You’d think that every read from the same address of memory should yield the same data result if that memory is implemented as ROM (read-only memory), right? Further, you’d hope that the values read from a given address match the corresponding bytes in the ROM image file, right?? Joël found that values the Game Boy CPU was getting didn’t match the ROM files and weren’t even consistent with themselves over time.

There was no bug in the Game Boy emulator, but there was a bug in our simplified understanding of the Game Boy hardware. Game Boy doesn’t exactly implement virtual memory, but it does have a system of dynamically configurable memory mappers that can expose different banks of the larger ROMs into the smaller CPU-visible address space over time. ROM banking is a technique used to access memory beyond a processor’s usual limits. For example the Game Boy uses a processor with 8 bit instructions and 16 bit addresses. With 16 bits you can address up to 2^16 or 65,535 bytes, which is about 0.065 Megabytes. To get around this limit, the Game Boy hardware uses a technique called “ROM banking” or memory mapping, which allows the programmer to switch between various parts of a ROM. On the Game Boy, addresses from 0x4000 to 0x8000 can be remapped to different ROM banks, allowing the Game Boy to address cartridges that are larger than 65,535 bytes.

With a better understanding of ROM banks, we were able to snoop writes to special memory ranges and interpret them as instructions to change the bank configuration. However, we were still seeing reads that disagreed with the ROM! After a lot of staring at code, we later found that even a memory read operation could actually influence the mapper configuration. You don’t expect reading a book to cause the chapters to get silently rearranged, but that’s how Game Boy works!

With the last ROM banking kinks worked out, we confirmed the precise mapping between run-time memory addresses and offsets into the fixed ROM files. Next we looked into starting to slice those files.

Here is how we first created a sliced ROM using a small Python script. Like taking a black marker to a copy of a book, we substituted a zero value for every ROM byte that wasn’t mentioned in one of our recorded memory transaction log.

import sys

import os

import pickle

if __name__ == '__main__':

filename = sys.argv[1]

base_name = filename.split(".")[0]

rom_size = os.stat(filename).st_size

rom = open(filename, "rb")

found = {}

pickle_file = f"{filename}.pickle"

with open(pickle_file, "rb") as input:

found = pickle.load(input)

# Copy cartridge header from original ROM to new ROM

# The cartridge header is the bytes from 0x0100 to 0x014F

for i in range(256, 335):

rom.seek(i)

found[i] = int.from_bytes(rom.read(1), byteorder='big')

zeroed_rom = f"{base_name}.0"

with open(zeroed_rom, "wb") as zeroed:

for i in range(0, rom_size):

if i in found:

val = found[i]

else:

val = 0

zeroed.write(val.to_bytes(1, byteorder='big'))

print("Done")

Meanwhile, Adam had created his own method to create sliced ROMs which, when combined with a save state, made a primitive playable quote that could be shared between ourselves. This was an exciting milestone for me since this was the first time that we were able to prove to ourselves that we could indeed create, play, and share Playable Quotes!

Another exciting discovery from this milestone was learning that we only needed to quote between about 3% and 13% of the original ROM to make a quote that was playable. These numbers have more or less held stable since we first did the measurements. We suspect that almost all machine code needed to support the game’s main gameplay mode gets included, but very little of the game’s overall artistic content (level designs, music, graphical sprites, etc.) get included.

Once we met this milestone, Joël decided to try out our technique with a variety of games since up to this point, we had only been testing our technique with Tetris, Metroid II, and Mole Mania. Joël wanted to make sure that the technique held stable across many different types of games.

Sadly, Joël discovered that PyBoy didn’t seem to work with the game “Alleyway.” This was a big letdown because we otherwise enjoyed working with PyBoy so much. We would need to switch emulators to gain wider compatibility.

Because of this discovery, we decided to try out a JavaScript based emulator called “GameBoy- Online” which had intimidating looking code and had not been updated in a while. Joël started by loading the GitHub repository for GameBoy-Online into Glitch and directly making some edits. To his surprise, it was actually pretty easy to get one of our PyBoy-derived Playable Quotes to work in GameBoy-Online! It was a huge hack, but Joël managed to do it by first playing to the point where he had created the Playable Quote in PyBoy (the first level in Mole Mania), taking a save state of that moment using GameBoy-Online, then combining it with the sliced ROM which had been created using Python. Save states aren’t compatible across emulators, but, by design, ROM files should be!

Meanwhile, Adam had been making progress by changing his code from writing a CSV file, which was really slow due to file I/O constraints, to an in-memory model which was much faster. This allowed him to prototype an interactive quote-editing widget that could visualize the range of memory needed to support a segment of recorded gameplay and also show you how much more gameplay could be accessed with the current memory slice.

This widget was slow to respond, difficult to share because it was written in Python (rather than JavaScript), and pretty inscrutible to anyone who wasn’t already familiar with low-level embedded programming concerns. This told us that there would be a high-end skill to crafting quotes with perfectly sculpted memory bounds, but it wasn’t going to help us communicate the idea to others very well.

By this point in the project, it was July 7th, a week since we had started on the project. The next day Adam and Joël were able to meet in person, since we had previously planned to go camping at the Tenmile Campground in Kings Canyon.

Tenmile Vision and Prototype

Something that this Playable Quotes project has really highlighted for Joël is how useful it is to regularly take time to check assumptions and do lightweight planning. It was unreasonably effective to have a few hours of distraction-free time to reflect on what we had learned so far, plan on what we wanted to do next, and clarify each of our goals for this project. (Adam is more familiar with this model from graduate student mentoring in his lab.)

Personally, Joël’s goals for this project came mostly from his interest in making better interactive media and also making tools to help people understand software. For Adam, his goals were mostly centered around wanting to demonstrate a notion of “snippets” of interactive media.

Encouraged by our recent progress in getting Playable Quotes working in both Python and JavaScript based emulators, we were able to start thinking about what to do next. Inspired by some of Adam and Kathleen Tuite’s previous projects projects like Sketch-a-bit and Feminist Hacker Barbie we agreed on working towards a vision of a site where people could load their own Game Boy games, as well as make and share quotes. We also wanted the site to be a vehicle for explaining the more abstract concept of Playable Quotes.

In short, we decided that we wanted to work towards three things:

- An academic paper (focusing on quotes as result snippets for search engines)

- A JavaScript library to allow anybody to embed a Playable Quote into any webpage (“jQuery for embedding Playable Quotes”)

- A webpage to allow people to create and share Playable Quotes (“Imgur for Playable Game Boy Quotes”)

Of those three goals, the last one is what we’ve completed so far in the form of the website you can see now at https://tenmile.quote.games

As someone who sometimes doubts the utility of his side projects, Joël found it really encouraging to see how Adam and Kathleen’s past projects were helping shape future projects. Inspired by Feminist Hacker Barbie, we wanted to make it easy to make new content via an in-browser casual creator tool that assumed no technical knowledge. Sketch-a-bit also inspired the “insert ROM to continue” functionality in our emulator, which, like in Sketch-a-bit, allows people to extend each other’s creations and turn consumers into creators.

With a clear vision of what we wanted to do, we had renewed excitement to help drive our work when we returned home.

Because we had decided on creating an in-browser tool, we shifted our attention to finding an emulator that could run in both desktop and mobile browsers, was compatible with enough ROMs to be interesting, and was also hackable enough for us to intercept low-level memory accesses.

Even though we already had a working proof of concept with the GameBoy-Online emulator, we weren’t sure if it met our criteria, so we spent some time looking around for others. However, none of the other emulators that we found met our criteria as well as GameBoy-Online did, so we eventually decided to stick with GameBoy-Online and see how far we could push it. The fact that GameBoy-Online is the emulator used by the friendly Game Boy game authoring tool GBStudio sealed the deal.

To our surprise, progress with the GameBoy-Online emulator went really fast. Thanks to JavaScript’s Proxy objects, Adam was able to quickly start intercepting low-level memory access, without needing to modify any GameBoy-Online code by writing code that looked like this:

gameboy.ROM = new Proxy(gameboy.ROM, {

get: function(target, prop) {

if (fsm.is("recording")) {

romAccessSet.add(prop);

}

return target[prop];

}

});

Thanks to Proxy objects, it was really easy to change the way that GameBoy-Online worked, without the mess of changing the code directly. Adam describes the technique as a kind of run-time aspect-oriented programming. Another major benefit of this approach was that we could be bold in our experiments without needing to worry about backing the changes out if they didn’t work, or accidentally breaking something.

From this point on, we kept pushing our code towards what we needed to make the website we had in mind. This meant learning to use Web APIs for Touch and Pointer events, finding and learning JavaScript libraries to read and write PNG files and ZIP files; serialize objects into msgpack data, and spending a lot of time browsing source code to GameBoy-Online to learn how it worked.

Eventually, we got to the point where it was clear that we had sort of painted ourselves into a corner and it was becoming frustrating to add new features. You could create quotes, drag them to and from your desktop, and grab control to play them. The project only involved about 300 lines of new JavaScript code on top of several libraries provided by others. However, each new layer of global variables and callbacks had to be tediously woven into the last. Adam suggested that we rewrite the code recycling only what we learned (rather than any code) and work on what we would eventually make public.

Production Mode

The main reason for the rewrite had to do with how we handled moving between the various modes like “playing”, “recording”, “saving”, and so on. This was all handled by a state machine, which only modeled a subset of the states we wanted. We spent some time figuring out what we wanted our new state machine to look like. Once we were happy that we had taken all states into account, we created a new project on Glitch that was built around those states.

The only feature that was left at this point was finding a way to make reproducible game replays. When a Playable Quote is being recorded, we keep a record of button presses. When the Playable Quote is loaded, we play those button presses back. If this is done right, the replay should look the exact same as the recording. But it wasn’t working for us.

This is still something that we’re working on. The way that we record and playback button presses sort of works today, but playing back the same button presses doesn’t result in an exact frame-by-frame reproduction of the original recording.

The initial problem was that we were only recording button presses at the end of each frame. In the process of researching the issue, Joël ran across a ROM that tests input timing called “Telling LYs?”. Upon loading this ROM into our Playable Quotes environment, it became clear that recording buttons presses at the end of each frame was the wrong way to go! The next thing we tried was making our own “tick” counter, which is incremented each time we call the run() function in GameBoy-Online’s inner loop. This is what we’re doing now, but it still doesn’t work perfectly! Please let us know if you know what we’re doing wrong. We suspect that it has something to do with the fact that button presses happen mid-scanline and there doesn’t seem to be an easy way to record and replay that information, at least none that we’ve found so far.

After struggling with getting reproducible game replays working for a while, we decided that it was good enough for a release, and decided to focus on polish.

For a brief period of time, Joël considered moving the project from Glitch to GitHub Pages or S3. Thankfully, he didn’t have to do any of that after realizing that putting CloudFlare in front of Glitch would be more than enough to handle whatever load we might get. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the best ones. One fun side effect of doing our project (and associated prototypes) on Glitch is that the history of our collaborative public development of the system is fully tracked.

As usual, adding the polish took a lot of work! Adam worked on making nice-looking PNG files for the Playable Quotes. Joël worked on making the emulator controls work on desktop and mobile, and Kathleen Tuite generously helped make the emulator look good (with rounded corners evocative of the plastic case on the original Game Boy hardware).

Once everything was code-complete we needed to make sure that we had interesting quotes to show off on the page, as well as text that attempted to describe what Playable Quotes are. Along the way we discovered that our code supported Game Boy Color games.

All that was left was creating a Twitter account to use to announce the project (and let people keep up with progress) and launching the site!

With all of that done, all that was left was announcing the project, which we did on August 13th:

For example, here’s a playable quote from the core gameplay of Tetris. You can stack blocks, clear lines, but you can’t complete a 4-line tetris because that behavior wasn’t included in the quote. https://t.co/R1gW3GxrtD pic.twitter.com/he2Om5y4iV

— Playable Quotes (@playablequotes) August 13, 2021

Suggestions for Future Work

We’ve only scratched the surface of what is possible with Playable Quotes, there is a lot more to do. More than we can do on our own, we could use your help!

Features that we could use help with include, but are not limited to the following:

- Get reproducible playback working on tenmile.quote.games

- Find better ways to show the player that they have tried to do something that isn’t part of a quote. Right now we simply do a reset, but there are certainly better ways to handle this!

- Get Playable Quotes working on other systems (Adam is already making progress on intercepting memory accesses in the 32-bit system emulator v86)

- Add gamepad support to tenmile.quote.games

- Also, feel free to reach out to us with other ideas or questions!

Advice

If you’re working on making your own Playable Quotes, here are some things that we hope makes your life a little easier:

Get save states working first. Remember: A basic playable quote is just a save state and a stripped down ROM. Try to intercept reads/writes as close to the memory as possible. This can be complicated if you do it close to the CPU core, which might only interact with memory through complex dynamic mapping systems. Use a state machine to handle transitions between various modes. It’s more useful than you might think! Get to a drag-and-drop interface as soon as you can. Development will get a lot faster once you do this. You can use quotes as test cases and share reproducible bugs quickly.

Thanks

We would like to thank the following people for their explicit or implicit help with this project:

Kathleen Tuite for adding Semantic UI to the project and using it to make the pages look professional.

The authors of the code we used to build this project:

- PyBoy

- GameBoy-Online

- Semantic UI

- jQuery

- Fontello

- Jszip

- pako

- UPNG

- msgpack

- State-machine

The team behind Glitch.

The folks who reviewed and gave feedback on early versions of the project including: Nato, Michael, Marcin, Ramón Huidobro and some folks who’d prefer to remain anonymous.